[N.B. This page replicates pages 110-126 of Chapter 6 from the PhD thesis, Britten the Performer: Aesthetics and Practice, by Simon Brown (Royal Birmingham Conservatoire). It is provided here to assist the reader with the analysis.]

Britten’s annotated scores

I shall now examine the source materials that are available for K.550 that will assist in the analysis. I begin with a description of these sources. I assess which of these Britten is most likely to have used during performance and the subsequent recordings that he made. I then provide an overview of Britten’s annotations, before looking at them in context, and discussing how these relate to the three recordings.

Overview of the printed source material

Britten owned four scores of K.550 and it is fair to assume the larger, study score, is the one that he used for conducting (see Table 6.2). This is not only due to its size but also the number of annotations, the condition of the spine and the corners of the pages being folded to ease with page turns. This is referred to as Source A. There are two miniature scores but only one of these contains annotations and is referred to as Source B. The fourth score is the NMA edition and does not contain annotations. Mozart revised K.550 with the addition of clarinets and changes in the existing oboe parts, and the NMA edition contains both of these versions. I usually refer to these collectively as the NMA edition but if necessary, the original version (without clarinets) is referred to as Source D1 and the revised edition (with clarinets) is referred to as Source D2. Source A is clearly based on the revised version, albeit with discrepancies as I shall reveal, whilst Source B reflects Mozart’s original.

In Source A there is an inscription inside the flyleaf by Imogen Holst. It refers presumably to the London memorial concert in 1959 and alludes to a standing joke between Britten and Holst who was by then his assistant. It reads:

For Ben,

(Adolph von Holst’s copy)

A thankyou for January 30th, 1959

With love from Imogen.

(Holst, inscribed flyleaf in, Mozart, 1882)

The inside cover contains a further inscription in Holst’s hand, made in pencil, and it presumably indicates the work that she had carried out for Britten:

The rehearsal letters agree with those in the parts.

The parts also have bar numbers at the beginning of each line.

(These have been put in pencil here against the Vln I line)

(Holst, inscribed cover in, Mozart, 1882)

| Source | A | B | C | D |

| Publisher: | Breitkopf & Härtel | Ernst Eulenburg | Wiener Philharmonischer Verlag | Bärenreiter |

| Place of publication: | Leipzig | London | Vienna | Kassel |

| Publication title: | Symphonies, no. 40, K 550, G minor | Eulenburg Miniature Scores No. 404 : Mozart, K.-V. No. 550, Symphony, G minor. | Symphonie 40 : G moll = G mineur = Sol mineur : Köch. nr. 550 | Sinfonie in g KV 550 |

| Editor: | Hellmut Federhofer | Unknown | Unknown | Landon |

| Plate/Catalogue number: | Mozart’s Werke: Serie 8; no. 40 | 3087 | W. Ph. V. 27 Edition/Matrix number: 27 | NMA IV/11/9: Symphonies vol. 9 |

| Publication date: | 1882 | [n.d.] | [n.d.] | 1957 |

| BPL Shelf Mark: | 11Ea3 | 11Ab3 | 11Ab3 | 1Kd1 |

| BPL ID: | 2-9104492 | 2-1000207 | 2-1000253 | [none] |

| Additional information: | 1 study score (49 p.); 35 cm. | 1 miniature score (66 p.); 20 cm. | 1 miniature score (66 p.); 19 cm. | 1 full score |

| Key features: | Britten’s conducting score Printed score; with annotations: pencil, purple crayon (Benjamin Britten). Version with clarinets. | Original covers and most details of publication absent, due to binding. Original version without clarinets. | Notes in German, English and French. No annotations. Original version without clarinets. | No annotations. Two versions, with and without clarinets. |

Rehearsal letters A-F have been written into both sources but it is clear that in A they were created by Imogen Holst. The rehearsal marks in Source B are in Britten’s hand and they match with those in Source A. Britten has inserted bar numbers in Source B, mainly at the beginning or end of each system, or at structurally significant points within the music. As Holst declared in the inscription, the bar numbers created in Source A against the first violin stave are in her handwriting. The remaining annotations are all clearly in Britten’s own hand in both pencil and purple crayon.

It has not been possible to establish the exact dates of when he acquired each of the scores. The inscription by Holst suggests that Source A was given to him around the time of the memorial concert in 1959, therefore it is possible that he used it for that performance. The fact that Holst inscribed the inside cover with details about the rehearsal letters and bar numbers matching the parts is further evidence to support this. The NMA (Source D, and the only other full-size score known to be in Britten’s possession) was published in 1957 so could not have been used for the Aldeburgh Festival performance in 1953 but the possibility remains that it could have been used thereafter. This seems highly unlikely due to there being no annotations within it and the spine is still intact. Of the two miniature scores (Sources B and C), it is likely that he obtained one if not both of these much earlier in his career, potentially even during his teenage years. In Source B there is certainly anecdotal evidence to support this. For instance, Britten’s annotations include several analytical markings such as the identification of the development section above b. 101 in the Allegro molto, or ‘link-episode’ above b. 228 of the same movement; the crossing out of the name ‘Edward Kennard’ on the title page, together with ‘W6’ enclosed in a box at the top of the page (perhaps denoting some kind of catalogue system devised by Britten as he collected these miniature scores); occasionally the handwriting appears to be that of a more youthful Britten. These are quite typical characteristics of someone trying to familiarise themselves with a work, although admittedly this is difficult to confirm with any certainty at this stage.

Overview of annotations

Assuming that Britten would have used Source A for conducting, do any of his annotations in this score replicate those in Sources B, or the editorial markings in C or D? Having done a comparative analysis of Sources B and C, I conclude that these are almost identical in terms of the printed dynamics and phrase markings. Therefore I concentrate my efforts on making comparisons between Sources A and B, and to see if any of these coincide with the editorial markings that can be found in the more trusted NMA edition (Source D). As with the analysis of K.478 it is important to discern if any of Britten’s annotations are merely transcriptions that he copied from one score to another or whether they are new or local decisions concerning interpretation.

I revealed in the previous chapter that there were a series of common traits to be found in Britten’s annotations of K.478. But could the same be said of K.550? There are certainly the same preoccupations with phrasing; sometimes this is achieved with specific phrase marks (either inserted anew or replacing, shortening or extending those that already exist in the score) but more often with crescendo and diminuendo marks or hairpins. Similarly, as might be expected of an orchestral score that has been used for performance, there is a great deal of significance placed on balancing the parts. This is achieved by making a number of alterations to the dynamics but also through the elimination of certain parts; occasionally Britten crosses out an entire part for several bars. Articulation is frequently applied, such as tenuto marks, including the occasional change on certain notes from staccato to tenuto, and whilst there does not appear to be quite the same level of concern between the staccato dot and staccato wedge that was witnessed in K.478, there are clear examples of differentiation between the two.

Practical considerations

In addition to the bar numbers and rehearsal letters that have been inserted, there are a number of other—what I consider to be practical—annotations that Britten created in order to assist him during performance. These might be thought of as large-scale or macro- rather than micro-annotations as they are less concerned with the details of how notes or phrases are to be performed but more with the structural elements of the score. For instance, Britten will frequently highlight if repeat marks are to be adhered too. This is usually done in one of two ways: either as a written instruction, such as ‘1st repeat’ that can be found at the top of the first page of Source A, or as brackets above and below the repeat marks, often accompanied with an arrow to indicate a return to the start of the repeat, as can be found in b. 100 of Source A. Britten also inserts vertical lines down the page to indicate a distinct change in mood, topic or character within the music, such as in b. 226 in Source B to mark the return of the second theme, or to indicate a rest or break between phrasing or sections such as the pause that Greenfield referred to in his review in bb. 238-239 but also b. 284 of Source A.

One of the most important structural aspects to this work that Britten has considered prior to performance was which version to use; either the original 1788 version or Mozart’s revised 1791 version with the addition of clarinets. Source A contains the clarinet parts and so presumably is based on Mozart’s revised version, but differs in important respects from the NMA editions (Source D). Furthermore, Britten has marked an ‘X’ against the clarinet part in purple crayon. Initially this might be thought to correspond with the programme note from the 1953 Aldeburgh Festival that was mentioned above and presumably indicates that if Britten was relying on Source A as the performance score, then he might be referring to Mozart’s original 1788 version without clarinets. But Britten crosses several parts out altogether throughout Source A and this suggests that, as he applied the pencil annotations, he was fully aware of the discrepancies between the scores.

The initial entry of the woodwind on p. 1 of Source A is an instance where Britten has crossed out the oboe part and written ‘Cl’ in pencil next to the clarinet part along with a crescendo and diminuendo hairpin starting at pianissimo. This instrumentation corresponds with Source D2 (Mozart’s revised version in the NMA), where the phrase is taken by the flute, two clarinets and two bassoons as opposed to the original version (which is also reflected in Source B) of flute, two oboes and two bassoons. The bars that follow this initial phrase in bb. 16-20 of Source A also reflects those of Source D2 but Britten marks the return of the oboes prior to b. 22. This would have been a visual reminder that the oboes should take this phrase and not the clarinets. A similar instance can be found on p. 3 of Source A where the oboe part has been crossed out and the letters ‘Cl’ are written to the side and above on the clarinet stave. The bassoon part also has ‘Bs’ written next to it and this is further evidence that Britten wanted the clarinets and bassoon to play this phrase as reflected in Source D2 (Mozart’s revised version), as opposed to the oboe and bassoon from the original 1788 version (and reflected in Source B and D1). Unless Britten had an in-depth knowledge of the score and was able to work from memory, this evidence suggests that he consulted at least one other edition, other than Source A, which he was using for performance purposes. It is fair to assume that from 1957 this would have been Britten’s own copy of the NMA.

That his annotations occur in two different inks, the purple crayon being much sparser than those made in pencil, suggest that Britten used this score on more than one occasion. It is understood from the programme notes of the 1953 performance that Britten performed the original version without clarinets, but we cannot be certain which edition he would have used. It is plausible that he borrowed an entirely different score but I believe it is likely that he worked from Source A; Imogen Holst had, after all, started working for Britten in September 1952. This would explain the cross next to the clarinet part at the beginning. If he was borrowing Source A before it was presented to him as a gift after the 1959 performance, it might explain why there are so few annotations in purple crayon. Of course, this might also be indicative of Britten’s early approach to the work, before he had access to the NMA edition and had ever contemplated whether to record the work.

Of the remaining annotations in the first movement of Source A that are in purple crayon, the most noticeable is concerned with the time signature at the beginning of the piece. In Source B the first movement is written in common time and whilst Source A is written in cut common time (which corresponds with both of the NMA editions), Britten has included a large number ‘2’ written across multiple staves and is a stark reminder to himself that the work begins with a feel of two-in-a-bar. Assuming the annotations in purple crayon refer to his first performance of the work, this might indicate Britten’s overfamiliarity with his miniature scores that were both in 4/4. It is apparent from the video footage of Recording B that Britten is conducting with a feel of two to the bar.

There are, as usual, too many annotations that Britten made in pencil to discuss all of them in detail. Therefore I shall be selective by highlighting just some of those that provide useful insights into how Britten prepared a score or those that I feel are most helpful to illustrate his decisions of interpretation. I shall concentrate mainly on the first movement but if there are annotations that I consider to be important to the reader from the other movements, or those that are relevant across several movements then these are also discussed. Not surprisingly with a large-scale work such as this, there will inevitably be many more points that one could discuss. The online resource has been designed so that other scholars, performers and composers can reflect on Britten’s annotations for themselves. As with my discussion on K.478, I focus on his phrasing, dynamics and articulation, but also his bow markings and how he achieved balance amongst the different sections of the orchestra. It is clear that Britten paid close attention to tempo throughout and I begin with an analysis of these markings before moving on to consider some of the other annotations in more detail.

Tempo

Britten typically employs two methods to indicate an initial or change of tempo. These are either a written instruction or a visual symbol as a reminder to follow a particular performance instruction. Arrows are frequently used, such as beneath the stave on p. 4 of Source A, as a reminder to push the tempo or not allow the music to slow. Similarly, towards the climax at the end of the first movement, Britten draws an arrow and writes ‘Tempo’, presumably as a reminder to pick up the pace in these concluding bars. Occasionally Britten gives specific instructions or reminders to himself such as ‘In tempo!’ or ‘too slow’ (see the bottom of p. 3 in Source A), for instance. At the beginning of the Andante he writes ‘flowing’ next to the strings (and the word ‘soft’ against the horns) whilst at the start of the Minuet and Trio he includes ‘in 3’ above the stave and then ‘Quick 3’ to the side of the staves, with the word ‘quick’ underlined for emphasis. There are no tempo markings at the start of the Allegro Assai but further arrows are to be found above the string section at the start of b. 71 (see p. 37 of Source A), above and beneath the strings in bb. 100-101 (see p. 38 of Source A), and above the strings in bb. 275-276 (see p. 48 of Source A). The significance of these arrows are that they always occur either during a crescendo, typically from piano to forte, or as the forte section gets underway. Most of these annotations are concerned with tempo changes within the music, or at the start of a particular movement. But what of the overall tempo of the piece and is there any relationship between certain movements?

Before I consider Britten’s choice of tempo for K.550, as evidenced from the recordings, it is worth briefly considering the preoccupation that Mozart had over the tempo of this work. My study of annotations and recordings suggests that Britten’s decisions on tempi are one of the most important aspects of his interpretations of works by Mozart and reveal his unusual insight that, to a certain extent, preempts the Historically Informed Performance movement.

According to Jean-Pierre Marty, in his seminal book The Tempo Indications of Mozart (1988), the autographed score of the first movement of K.550 is evidence of Mozart changing his mind about the tempo of this work.

Besides the Augsburg letter, we have many other proofs of Mozart’s keen interest in the crucial question of tempo. Other letters contain precious indications, particularly in connection with his own works. We also have the evidence of his manuscripts, on which a first tempo indication is often crossed out to be replaced by another, which may appear to us to be of practically the same meaning; such as, for example, the case in the first movement of the G-minor Symphony K.550, where he replaced the original Allegro assai, with Molto allegro. (Marty, 1988, p. x)

The Augsburg letter that Marty refers to was sent from Mozart to his father dated October 24 1777. In it Mozart stresses the important role that tempo has in music and therefore, by inference, in his own music. He is reporting to his father on a performance that he witnessed of the daughter of the instrument maker, Johann Andreas Stein (1728-1792). Marty’s translation of Mozart’s letter reads ‘She will never achieve the most necessary, the hardest, and the main thing in music, namely Tempo, because from her very youth she made sure not to play in time’ (Marty, 1988, p. ix). I believe Marty rightly concludes from this that Mozart draws a clear distinction: that playing in time is not the same thing as achieving the more allusive element of playing at an appropriate tempo. Marty argues that

Tempo suggests an idea rather than expresses a clear concept. This vagueness, inherent in the word, is even increased in Mozart’s letter by the three superlatives, with which he attempts to pin down the notion: “the most necessary,” “the hardest,” and finally “the main thing in music.” (Marty, 1988, p. ix)

The reason I include this short digression is to illustrate the attention and importance that Mozart appeared to place on the tempo of his works in general, and as I shall reveal, the relationship between the first and last movements of K.550 in particular. Whilst Britten could not have been familiar with Marty’s work, this same level of attention and due diligence to his tempi is common across many of Britten’s annotated scores, both in works by Mozart and by other composers. However, Marty makes another interesting and pertinent observation about K.550:

The first movement of the G-minor Symphony K.550 […] could conceivably be taken (and frequently are [sic]) at a very high speed. No technical obstacles stand against such a possibility. But a very precious clue on the manuscript […] proves to us that it should not be so. The first indication written by Mozart at the beginning of the G-minor Symphony was actually Allegro assai; he later crossed out the qualification and replaced it with [Allegro] motto. There is therefore not a shadow of a doubt that the two qualifications were not synonymous in his mind. Allegro assai was reserved for the finale of the symphony, and a distinct difference in tempo should be observed between the two movements. (Marty, 1988, p. 160)

So how does this relate to Britten’s interpretation? The first thing to note is that Britten draws a line between the words ‘Allegro’ and ‘molto’ on the first page of Source A. This appears to underline the word ‘Allegro’, making it distinct from the word ‘molto’. I believe this is a clear indication that Britten understood that the first movement should be performed slower than the last. He may have consulted the NMA as both versions in Source D read ‘Molto Allegro’ for the first movement and ‘Allegro assai’ for the last. In the critical report to the NMA, Landon (1963, p. i/24) highlights that Mozart corrected his original tempo markings in the autographed score. Whilst the publication date of the scores was 1957, the publication date for the critical report was not until 1963 (Landon, 1963, p. i/24). Therefore Britten could not have had access to the report for the 1953 or ’59 performances but it is feasible, and I would argue highly likely, that he consulted the report for his later performances of the work, from 1963 onwards. Of course, Britten’s precise tempo can be easily verified by the recordings. Table 6.3 compares the starting tempi of the first and last movements in each of the three recordings.

| Recording | First movement (start) | Last movement (start) |

| A: LSO, 1963 | 104 bpm | 138 bpm |

| B: ECO, 1964 | 109 bpm | 145 bpm |

| C: ECO, 1968 | 108 bpm | 140 bpm |

Whilst all three recordings are consistent with what Marty considers to be a more faithful interpretation of K.550 with the last movement noticeably quicker than the first, what this also reveals is that the only recording that was published during Britten’s lifetime sits between the other two in terms of their tempi. The differences are admittedly subtle but I believe this is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that reveals why Britten might have been dissatisfied with the 1963 LSO recording; despite the slight difference in beats per minute between Recordings A and C, the opening tempo of the first movement of Recording A is noticeably slower than in C. It is plausible that Britten considered the first movement of Recording A as being too slow and the last movement of Recording B as too fast. There is no evidence to suggest that Recording B was ever intended to be released commercially, but bearing in mind that it was broadcast live on the radio and then a year later on BBC2 television, presumably Britten would have been in a position to reflect on both Recordings A and B at some stage, before making the 1968 recording that was published.

It is interesting to note that after the 1963 LSO recording he decided to perform the work prior to each subsequent recording. The first public performance was at the Lucerne Festival in Switzerland just months before the live radio broadcast was scheduled in 1964. He then chose to perform it again during the 1967 Aldeburgh Festival ahead of making the 1968 recording at the Maltings, which was published the same year. Considering his care with the tempos throughout K.550, as evidenced by his annotations, it is not surprising that the success of a performance, in Britten’s own mind at least, would have been largely down to the tempi that he established and how this fitted with the various inflections throughout the piece.

Dynamics

Of the annotations throughout the source material for K.550, Britten’s alteration of the dynamics are the most frequent. In both Sources A and B Britten often extends the printed dynamics, for instance changing a piano to pianissimo. At the other end of the spectrum (i.e. changing a forte to fortissimo) it is less common, but there are many more subtle changes to be found. I shall begin by looking at whether Britten’s stylistic traits that were discovered in K.478 might apply here, before considering what the dynamic markings might tell us about his approach to preparing a score.

It was evident from K.478 that Britten would frequently use hairpins to shape a phrase, usually highlighting the registral peak or trough of the phrase with an increase in dynamics. This stylistic device continues in Britten’s annotations of K.550. In Sources A and B he frequently marks crescendo/diminuendo hairpins throughout the phrases; for example, the opening phrase in bb. 2-5 of Source A in the violins and this is replicated in Source B. These are not found in either editions of the NMA (Source D) and are therefore Britten’s own performance directions. A similar hairpin can be found in the next phrase between bb. 5-9 of both sources but Britten marks the second phrase to begin pianissimo in Source A (i.e. quieter than the first phrase). There appears to be a tick next to this, which may indicate that he deliberated over whether to play or at least begin the second phrase quieter than the first, and presumably decided to proceed with this interpretation at some stage. However, Britten does not adhere to this in any of the recordings; in fact, in Recordings A and C he does precisely the opposite by raising the dynamics in the second phrase. This is further supported by the crescendo under the cello and bass stave in b. 6 of Source A, which is not found in Source B.

The hairpins in the opening phrase of the first movement are indicative of how Britten uses this device but similar instances of either crescendi or diminuendi occur throughout K.550 and they are particularly effective in the opening bars of the second movement.6 After the opening quavers in the strings and the entry of the horns in b. 4 of Source A, the quaver-crotchet-quaver motif taken by the violins in bb. 4-5 are marked with a diminuendo hairpin. It is obvious from the second occurrence of this phrase in bb. 5-6 that Britten intends to be very precise about where this should commence. He initially writes a diminuendo hairpin at the start of the phrase but subsequently corrects this with the effect that the diminuendo begins on the crotchet and ends on the final quaver, as did the previous phrase. I believe this short but very effective shaping of the phrase is just one of the ways in which Britten achieves what he described as ‘the dark quiet of the second movement […] impelled by an unspeakable sorrow’ (Britten, 1967, p. 36). The lack of printed crescendo/diminuendo markings in the NMA edition is striking.7 Britten’s use of this device is important as it reveals his own decisions of interpretation unswayed by editorial markings. But is there evidence that Britten copied dynamics from one source to another?

There is a handwritten note at the top of p. 3 of Source A that is crossed out but reads ‘(not found in [Bärenreiter?] ed.)’. Underneath this is an arrow pointing to the printed sforzando, and to the side Britten has written a large fortepiano. Presumably indicating that his own performance direction applies across all staves being as they all share the same printed dynamic. This is interesting for two reasons: firstly, despite the fact that Britten’s handwriting is partly illegible, it does indicate that Britten was consulting multiple copies of the work, comparing these particular aspects and making notes about any discrepancies that occurred to him. Secondly, it also illustrates that Britten was not merely accepting the NMA edition and was making decisions based on his own interpretation. The sforzandos can be found in all of the sources (including both editions in the NMA) and yet, notwithstanding this, he still decided to alter these to fortepiano. Whilst this might seem to be a subtle difference, it is indicative of precisely the level of detail that Britten would consider when annotating a score.

A further comparison of the dynamics between Sources A and B in bb. 103-111 of the first movement reveals an example of where Britten changes his mind, something that is not unusual in his annotated scores. In b. 102 the printed dynamics match in all sources (indicating piano) but in both Source A and B Britten has changed the piano to a mezzoforte (written above the flute in Source A and beneath the bassoons in Source B, but presumably referring to the entire section as the printed dynamics are the same across all instruments) followed by a diminuendo as the strings enter in b. 103. At b. 103 of Source A Britten has originally inserted a pianissimo marking followed by a crescendo above the violin stave. Both of these are crossed out and replaced with mezzopiano and a diminuendo. Whilst neither of these dynamics are found in Source D, the diminuendo is marked in Source B. Britten is clearly paying close attention to the balance between the woodwind and the strings. In Source A he includes a crescendo from the piano beneath the cello and bass stave, which appears to contradict that which is above the first violin. As the viola, cello, and bass are not playing in these bars it is not clear whether this is an overriding dynamic, reverting back to the printed suggestion, or whether it is likely to be a visual cue in anticipation of what occurs just prior to the lower strings’ entry over the page in b. 105.

In the bars that immediately follow, Britten’s deliberation of how to shape the melody is still apparent. In b. 106 of Source B it appears as though he began writing a diminuendo and then changed his mind halfway through applying it to the score, resulting in an ambiguous annotation that could be construed as either a diminuendo but more likely—following the natural flow of the pencil mark—a crescendo.8 This indecisiveness is replicated in bb. 106-110 of Source A; two crescendos in bb. 106 and 108-109 have been crossed out and replaced with diminuendos, whilst the diminuendo in b. 110 is reverted to a crescendo. All of these concluding or final annotations match those in Source B. It is interesting to note that his dilemma of whether to have a crescendo or diminuendo through the antecedent phrase of the theme was first seen in b. 21 of Source A above the violins. Here Britten has concluded with a crescendo but it has clearly been changed from a diminuendo and the latter reflects the annotation found in b. 21 of Source B.

Another form of dynamic marking that Britten applies is verbal comment. For instance, as the first movement comes to a close on p. 18 of Source A, Britten calls for restraint by inserting ‘non troppo cresc’ between the flute and oboe parts. Abbreviations are sometimes used instead of symbols, such as the ‘dim’ written in bb. 111 and 112 of Source A or the ‘cresc’ in bb. 187-188. Occasionally the written descriptions imply more than just dynamics, such as articulation that is to be performed in a certain way, and they usually act as a reminder to himself that a particular passage should be played with a certain feel. For instance, at the top of p. 13 of Source A Britten writes ‘lightly’ and it is clear that this is achieved not just through the dynamics but the articulation and bowing.

Articulation

The most pertinent question concerning articulation is whether Britten makes a similar distinction too that made in K.478 between the staccato dot and staccato wedge. It is worth noting that neither Sources A or B include any printed staccato wedges and, as might be expected on Britten’s annotated orchestral score, there is less concern as to whether a wedge might be perceived as fingering (as was potentially the case with K.478). Therefore any staccato wedges that are included by Britten in K.550 would be a significant step forward in proving that he did make a distinction between the two. Considering the relatively few annotations on Source B (particularly in comparison to A), it is not surprising that no wedges are to be found. There is evidence of Britten applying them to Source A but it is not quite as straightforward as it might first appear. I shall begin with looking at examples of staccato dots before considering the issue of the staccato wedge, whilst simultaneously examining his use of tenuto. As with Britten’s application of dynamics, it is useful to identify any patterns or stylistic traits that might arise and these are considered alongside each type of articulation.

Examples of staccato dots

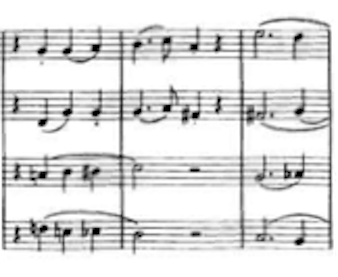

A good example of Britten’s focus on staccato markings can be found in bb. 229-230 of the first movement. There are discrepancies amongst the different sources. In Source A, Britten has inserted a staccato dot above and below the A and F# in the violin parts of b. 230 and circled these to highlight them. Drawing a circle around his own annotations is not something Britten did as a matter of course, so the fact that he does so here draws further significance to them. In Source B there are no staccato markings (either printed or annotated) over these notes. In both Source D1 and D2 they are included, but in both instances the staccato dots are much smaller than is customary, indicating they are an editorial edition (see Landon, 1963, p. vi). Compare these to the standard staccato dot that can be found beneath the G in the second violin part in b. 229 of the NMA (see Example 6.1). Similarly, beneath the G on the first beat of b. 229 in the first violin part of the NMA. This printed staccato dot is included in Source A and B. Britten leaves this intact in Source A but adds a tenuto mark above it. The G on the final beat of b. 229 also lacks a staccato dot in Source B, but the dot is included in Source A and the NMA; perhaps because this is of the standard weight in the printed version of Source A Britten does not feel the need to highlight it here. Example 6.1: Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K.550, bars 229-231 of the strings (from top to bottom: Vln1, Vln2, Vla and Vlc/DB), from the NMA edition (Source D2).

Example 6.1: Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K.550, bars 229-231 of the strings (from top to bottom: Vln1, Vln2, Vla and Vlc/DB), from the NMA edition (Source D2).

There is further evidence of Britten questioning the printed articulation in Source A. In the final bars of the Andante, Britten highlights the last notes of a repeated phrase in the bassoon and horn parts in bb. 119-221. The staccato dots are crossed out here, and above the stave Britten has written ‘no dots’ with a line to each part. These coincide with an early occurrence in bb. 48 and 50 of the Andante, where Britten includes the same instruction ‘no dots’ with arrows, but does not cross them out. I believe this is further evidence of Britten consulting alternative editions of the score as it would be an unusual coincidence if he simply decided that those particular notes should not be played staccato. By writing ‘no dots’, in addition to crossing them out, he may also be referring to the fact that they are not included in the NMA edition. Indeed, they are not included in either the NMA editions or Source B but it would seem odd if Britten held the latter in higher regard than the NMA. A similar annotation occurs towards the end of the Menuetto of Source A. In the right-hand margin after the double barline Britten has written ‘heavy [illegible] – no dots/’. By comparing this to the NMA edition it becomes apparent that it refers to the woodwind in bb. 34-35. On this occasion staccato is included in both Source A and B but not in the NMA and therefore, as with the Andante, this provides further evidence that Britten was consulting the NMA.

Examples of staccato wedges

In b. 115 of the molto allegro in Source A there is evidence of Britten’s awareness of the staccato wedge in the NMA but he chose not to apply them to his conducting score. Above the oboe and clarinet staves Britten has drawn a circle around the staccato dots in Source A to highlight them. In the NMA these are wedges and similar instances appear in bb. 119 and 123, but in Source A Britten only highlights their first occurrence. Nevertheless, by circling them Britten is clearly acknowledging that there is, at the very least, a question over them. It might also refer to the contradictory notation that a staccato minim implies, however, I believe that by highlighting them Britten reveals that he is aware that wedges exist in the NMA, despite his decision not to copy them into Source A.

What is most striking about this issue is that there are no instances where Britten has copied staccato wedges that occur within the NMA into Source A. This might lead to the conclusion that he was not making a distinction between the wedge and the dot but, as I shall reveal, there are instances where Britten has written a wedge. Furthermore, Britten has written ‘Staccato’ at the beginning of the Allegro assai and certainly in the opening bars of this movement staccato dots are used exclusively in the NMA. It is only between bb. 126-132 that staccato wedges appear in the NMA (see Example 6.2) and in the critical report Landon highlights the ambiguity of whether staccato wedges or dots should apply in these bars (Landon, 1963, p.i/41). If Britten was aware of the issue in these bars, he chose not to copy the wedges to Source A. This does not detract from the fact that he was aware of the difference between the dot and the wedge, and that if he thought the wedge was more appropriate then he would apply it, even if it was not found in the NMA. Example 6.2: Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K.550, bars 125-132 of the allegro assai, from the NMA edition (Source D1).

Example 6.2: Mozart, Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K.550, bars 125-132 of the allegro assai, from the NMA edition (Source D1).

In bb. 17-19 of the first movement of Source A Britten has written staccato wedges above the top stave. These are not included in either versions of the NMA and they therefore illustrate Britten’s idiosyncratic use of the wedge. He also marks a curved bracket around the woodwind chords, presumably to further highlight that they should be detached, thus leaving the string section, which Britten has marked with a tenuto above the first violins, to hold the sustained chord. In b. 66 of Source A there are wedges above the flute, bassoons, first violins and violas, whilst in the NMA there are no dots or wedges over any of these notes. Similarly in bb. 96-97 there is another instance where Britten has annotated a staccato wedge that is not found in the NMA. Here the slurs in the first violins have been crossed out and wedges applied to the first pair of quavers in each bar.

What has become apparent from a close reading of Britten’s scores (of both K.550 and others) is that the frequency of his annotations makes it unfeasible to discuss the precise implication and meaning of each individual one, at least, to serve them justice, and furthermore, multiple interpretations of the same annotations might be possible. What have also become apparent are the common traits, similar to those found throughout K.478; his preoccupation with phrasing through the use of either phrase marks, dynamics and articulation. Whilst there is not quite the same level of focus between the staccato dot and wedge that we witnessed in K.478, there is still evidence that Britten made a distinction between them here; his concern over the tempi of each movement and how these relate to each other; and his concern over the balance of the orchestra, achieved mainly through dynamics but also his choice of the instrumentation (i.e. which parts should be playing a particular phrase). In the final section of this chapter I consider how two of these traits are evident from the recordings.

[N.B. That concludes this online section of Chapter 6. Please return to the paper-based version of the thesis and continue reading from the section heading ‘Recordings’ on p. 126.]

Footnotes

6 It is useful to differentiate between the hairpin and the verbal indication of ‘crescendo’ or ‘diminuendo’, not least because the former has a specific beginning and ending, whilst the latter, in itself, does not specify the point of termination. With a few exceptions (see below), Britten elects to use hairpins. [Return]

7 There are no hairpins included within the NMA edition and only the occasional crescendo or diminuendo are written out, such as in bb. 62-63 of Source D. [Return]

8 Despite being reportedly left-handed (see ‘One hundred famous left-handed people’, The Guardian, 13 August 2003 [Online]. Available at http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2003/aug/13/2 (Accessed: 1 March 2016), Britten was in fact right-handed. According to Jonathan Manton, a Cataloguer working on the Britten Thematic Catalogue Project at The Britten–Pears Foundation, ‘there was a short period of time where [Britten] had to use his left hand to write after he sustained an injury to his right arm but other than that always wrote with his right hand’ (Manton, n.d.). [Return]